One of the challenges in building an interactive voice bots is accounting for turn taking behaviour. Turn-taking is a difficult problem to get right, even for humans. In all our circles, we’d know of at least one person who likes to interrupt a lot and doesn’t have good turn taking etiquette. Having a conversation with such a person can be quite irritating as one feels one is not getting heard or even getting a chance to finish one’s sentence.

Turn-taking is even more difficult in a multi-party setting. You might remember the last group call you had and just when you were about to take the turn, someone else jumped right in (because you waited for a tad bit too long) and you never got to speak. Turn-taking behaviour also differs culturally. In some cultures, interruptions and barge-ins are a lot more natural. There is also a difference in the inter-turn pause duration. These factors often lead to an unnatural conversation flow when speaking to a person from a different culture.

Note : Bots with explicit turn-taking signalling like wake-words are out of scope for this blog.

Natural Turn Taking Dynamics

Irrespective of nuances, there are aspects of turn taking behaviour which are globally present in natural human-human conversation and one’s that we would want to imbibe in a human-bot interaction as well.

- Barge-ins: These are situations when one agent interrupts the other. They occur very commonly. Examples of situations are : when one feels the other person is making a mistake or when ones feels the need to add some essential information, one naturally barges in.

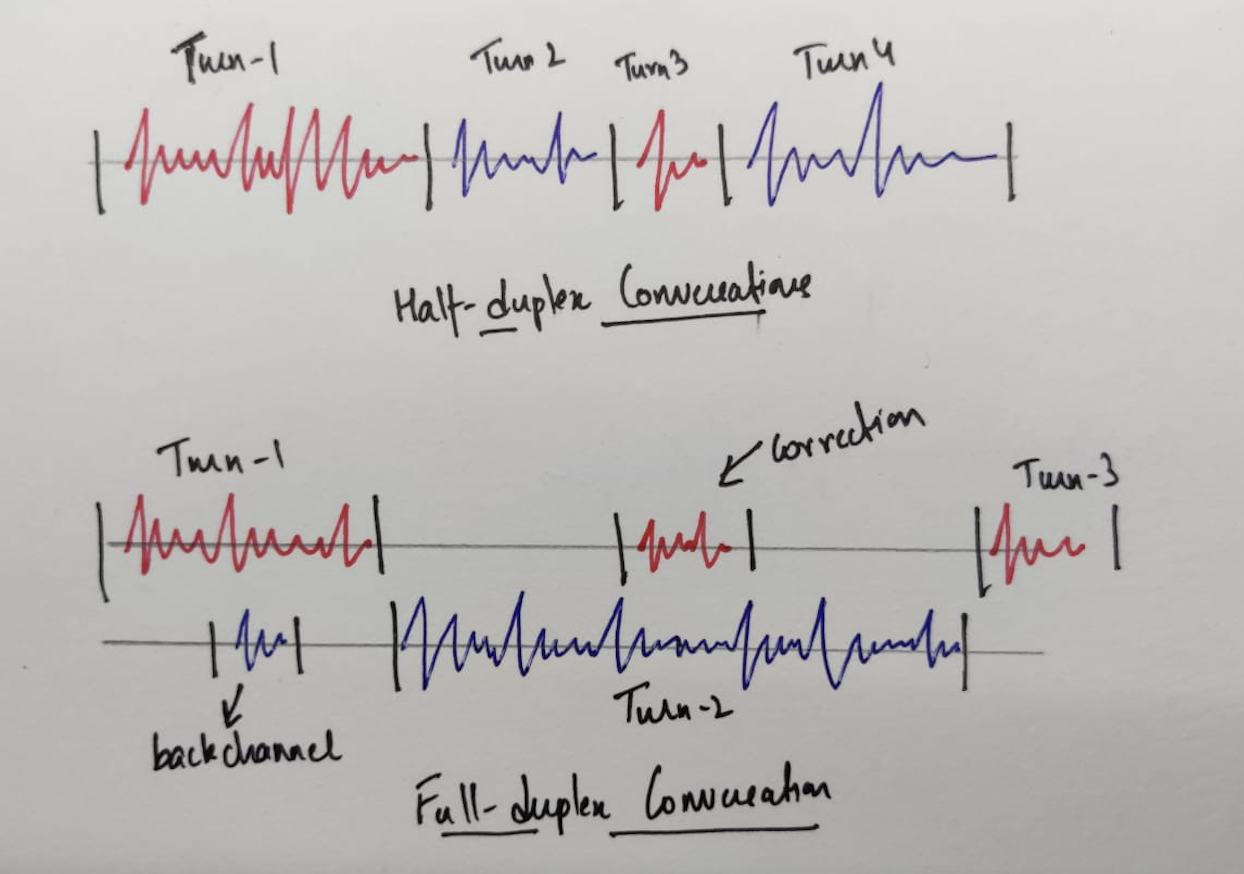

- Full Duplex Conversations : A half duplex conversation is one where turns are alternatively taken, like playing a tennis match, however in natural conversations, there are often instances when both people are saying something at the same time.

- backchannels : words and fillers like “okay”, “alright” or “hmm” provide a lot of context about the state of the other person(for example attentiveness), especially when one is talking over the phone and visual cues are absent.

- corrections : at times, when a person is saying something, one might want to make a small correction. For example, if there is an announcement being made “for the next meeting, you are supposed to finish submissions by 12th December, at so and so time….”. When the person is saying 12th December someone might correct by saying 13th December. This information is assimilated by the person and they often correct themselves. So, humans have the ability to hear and understand even while speaking and are active listeners.

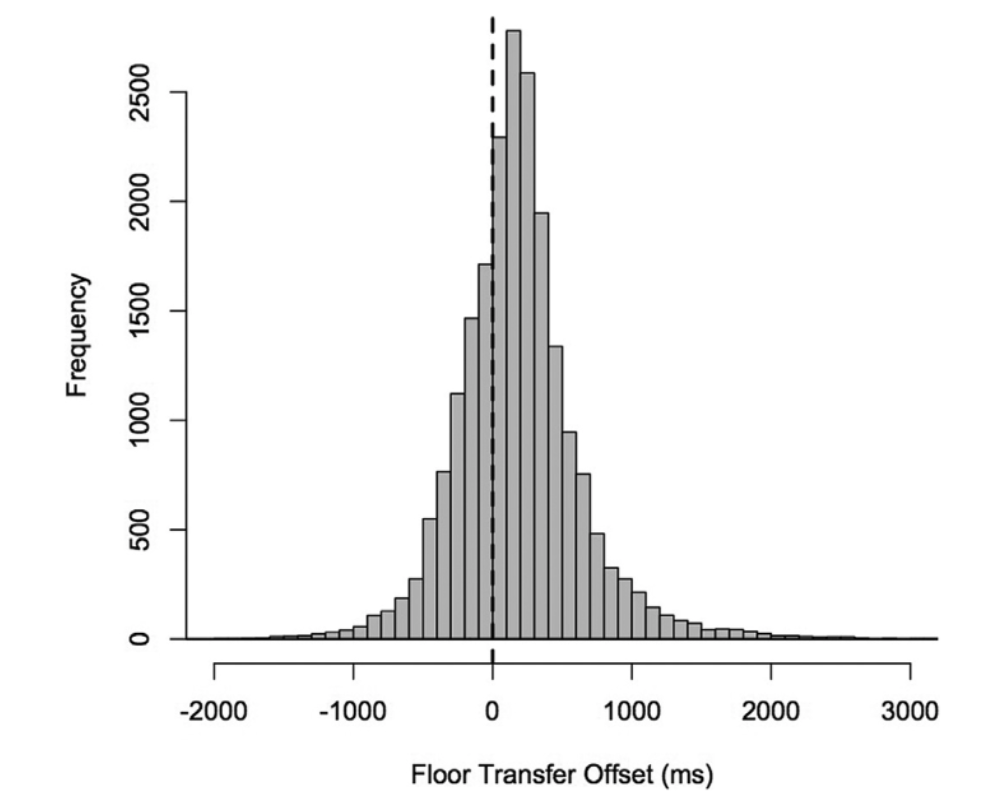

- Minimal inter-turn pauses : if you’ve ever spoken with a voice assistant, one of the first observations is that it takes too long to start speaking after you are done and the other way around. Human conversations have a much lower turn taking latency. If this latency is near optimal, it also lends to a feeling that the other person is understanding you and the left over impression is that of a conversation gone well. Human’s have an average pause duration of 200ms as shown below, while bots have a much higher latency.

- Turn taking cues : often in natural conversations, people produce small vocal cues like filler words “umm” or “uhhh” to convey that they want to say something and take the turn.

- Turn yielding cues : there are markers is conversations when one knows that the person is done speaking. This is how we are able to separate pauses, which happen when a person is thinking in between his utterance vs one when he is done speaking.

Turn-Taking Dynamics in Voice Bots

Below, we discuss different versions of turn-taking dynamics implemented in voice-bots each with more features and increasing levels of difficulty.

Version - 1.0

These are some characteristics of a bare bone turn-taking behaviour that one would need in a voice bot deployment.

- Initial patience : the time that the bot waits for the person to starts speaking

- Silence detection : if the bot detects silence for a certain duration after the person has started speaking, it assumes the person’s turn is over.

- Max turn duration : it doesn’t make sense to just be listening (because of error compounding, loss of context, maybe one is hearing just noise), so usually voice bots have a maximum duration to which they listen to the user.

Version - 2.0

This version add robustness for real life situations, make the bot more human-like and tries to reduce the latency between turns.

- VAD instead of silence detection : Often existence of background noise, speech and other signals causes the bot to keep listening. Instead one could train a Voice-Activity Detection system rather than use silence detection, to have robustness to background events and to listen to the user only when they are speaking.

- Variable thresholds for silence detection and max duration : In some states for example, when the bot is expecting a yes/no answer, it makes sense to use smaller thresholds. In general dynamic thresholding should be used.

- For turn-switching, instead of a simple VAD, use an IPU based model discussed here. This uses a smaller VAD threshold + cues to predict the turn is over. One could start with some verbal cues for example phrase completion.

- Adding backchannels as bot responses : So far we’ve only discussed aspects of perception, but backchannels are a very useful response feature. It makes the user feel that the bot is more attentive and is actively listening.

- One could also add filler words in the main channel, when the bot is taking too long to produce a response in cases of high latency. This would prevent the user from asking a question to verify if the bot is there or not. Without this, the user’s speech would lead to further increase in latency as it would be perceived as a case when the user wants to take the turn and say something useful.

Version - 3.0

There are no good baselines for these and working on improvements would constitute state of the art performance.

- Multi-party situations : These are a lot more complex and require modelling multiple parties. An application could be when the bot is overseeing a human-machine interaction say, between a call centre agent and a human. Another common use is when during a typical 2 party interaction, someone interrupts the user. This requires the bot being aware that the user is speaking to someone else and then waiting.

- Full - Duplex Conversations : Unlike human-human conversations a bots can attentively listen at the same time, while saying something. This offers a possibility of redesigning interactions which can leverage this feature.

- Personalisation of Turn taking behaviour : This involves changing the parameters based on user characteristics. One could entrain one’s system to be more in line with the user’s behaviour. At times when the user is angry it might involve changing the durations to feel that they are being heard.