In this post, we will discuss the phenomenon of speaker entrainment and the insights we gained when designing a voice-bot that entrains on the user’s speech. This work was done by me as a ML Research Intern at Skit, supervised by Swaraj Dalmia.

Introduction

Speaker Entrainment (also known as accomodation or alignment) is a psycho-social phenomenon that has been observed in human-human conversations in which interlocutors tend to match each other’s speech features. Believed to be crucial to the success and naturalness of human-human conversations, this can look like matching style related aspects such as pitch, rate of articulation or intensity, or content related factors, such as lexical patterns.

This phenomenon essentially helps one manage the social “distance” between the two speakers, and hence serves to build trust. This trust has the potential to increase call resolution rates and improve customer satisfaction in task-oriented dialog systems.

Much research has gone into what features are relevant for speaker entrainment, such as phonetic features [1], linguistic features such as word choice [2], structure/syntax [3], style [4] and acoustic-prosodic features (pitch, intensity, rate of articulation, NHR, jitter, shimmer) [5, 6, 7].

Based on this, our research work in this project aims at building a baseline bot using low-level understanding of the above features to establish the statistical significance of speaker entrainment as well as understand its potential to improve customer experience. We also publish a demo to show what this looks like in real-world conversations.

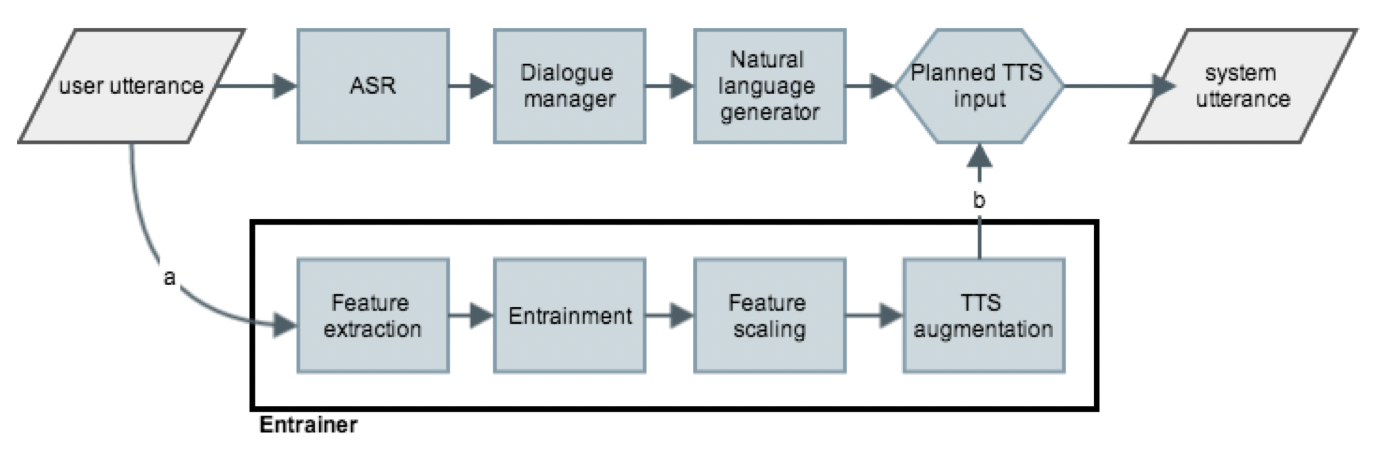

Methodology

There have been a few implementations of speaker entrainment modules in research, such as Lubold et al. (2016) [8], which discusses a system of entrainment based only on modelling pitch and Levitan et al. (2016) [9] which details a system based on \(f_0\), intensity and rate of articulation. Subsequently Hoegen et al. (2019) [10] discusses a system of modelling acoustic and content (lexical) variables separately, and Entrainment2Vec (2020) [11] details a graph based model of entrainment with vector representations in multi-party dialog systems.

For our baseline model, we choose mean \(f_0\), intensity and rate of articulation (calculated by utterances/sec). We average over these over the past three utterances (two speaker utterances and one bot utterance) to calculate the value for next bot utterance. This is inspired from [10] and prevents drastic jumps in the bot’s voice profile, which might lead to unnaturalness. For the value of any feature \(F\) at turn \(i\) we have,

\[F_{bot, i} = \frac{F_{user, i-1} + F_{bot, i-1} + F_{user, i-2}}{3}\]as the value of the feature at \(i\)-th turn in the bot’s speech.

Experimental Setup

We record 11 scripts with varying measures in each of the three features (e.g. pitch rising, intensity low/high, rate of articulation low) and one with an angry user using the entraining bot and a control bot which does not entrain. We involve 30 participants in this experiment who are asked to rate the bots on factors such as likeability and naturalness. We then conduct a paired right taled t-test to determine the statistical significance of speaker entrainment over the three features and combinations thereof.

The questions have been inspired from Shamekhi et al. [12], which are posed comparatively, e.g. “Does Bot A sound more natural than Bot B?”. These are answered on a comparative scale as well (from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree) to encourage decisiveness in differentiation among participants. Note that if one assumes the comparative scale comes from a difference of scores that the participant evaluates internally, the paired t-test can still be conducted. This is because if we assume \(X_C\) to be the comparative score arising from the difference of \(X_A\) and \(X_B\) (score for Bot A and Bot B respectively), we have,

\[X_C = X_B - X_A\]Note that for performing a t-test we only need the difference in mean and the sum of squares of standard deviation.

\[t=\frac{E[X_B]-E[X_A]}{\sqrt{\frac{Var(X_B)}{n}+\frac{Var(X_B)}{n}}}\]This can be easily rearranged to

\[t=\frac{E[X_c]}{\sqrt{\frac{Var(X_c)}{n}}}\]With this t-value, knowing what side of the tail our data lies on, we use the right tailed cumulative distribution and calculate the p-values accordingly.

Results

We find that the entrained bot performs better than the non-entrained bot in most cases. Keeping our \(\alpha=0.01\), we reject the null hypothesis for entrainment in multiple feature-sets, namely: pitch, intensity, pitch and rate of articulation combined and loudness and rate of articulation combined. In most other cases, including that of the angry user, we find that the entrained bot performs better as well, however the p-values aren’t as signficant. There are cases when the non-entrained bot performs better than the the entrained bot, but they have a large overlap with the cases in which our perception module performs inaccurately, e.g. rate of articulation is higher in shorter utterances due to lesser number of silent periods.

Issues

There are a few issues with our investigations in terms of the insights we can draw. Firstly, in cases of the entrained bot performing better, it is difficult to disentangle whether this is a result of the changed voice sounding better in absolute (e.g. perhaps the participants have a preference to higher pitched/faster speaking voices as a result of shared socio-cultural factors).

Secondly, in the cases of entrained bot performing worse, it is again difficult to disentangle if this poor performance arises from entraining poorly or whether speaker entrainment over this feature leads to bad performance in general.

Future Work

Levitan (2020) [13] is an inspiration of future directions in speaker entrainment research. So far, there is a significant lacunae in speaker entrainment research as far as incorporation of deep learning is concerned, be it in the perception module (i.e. rich representation spaces for audio) or control module (TTS with a natural control over features and emotions).

Classifying user speech should also be incorporated to understand the degree of entrainment that is necessary, rather than just entraining for every user, which can look like discriminating based on the style of conversation such as High Involvement and High Consideration (described in Hoegen et al. [10]). This layer of classification serves to decide the quality/degree of entrainment, which has the potential to improve customer experience. Furthermore, this layer can help detect angry/dissatisfied users as well to plan appropriate course of action by detecting high intensity speech, hyper-articulation, etc.

One can stand to improve the quality of experimentation as well. Apart from having more granular options for providing opinions (like a 7-point scale), we can have more speakers as users and more voice profiles for the bot to disentangle the experiment’s results from inherent voice qualities. Moreover, any improvement in the entrainment module will improve the quality of results as well.

Conclusion

Many psycho-sociologists deem speaker entrainment to be crucial to naturalness and trust building in human-human conversations. Recent advancements discussed in Levitan (2020) [13] imply that speaker entrainment is more nuanced than previously thought, but this means if implemented and modelled well, speaker entrainment has the potential of significantly changing the way voicebots interact with users.

References :

[1] J. S. Pardo, “On phonetic convergence during conversational interaction,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 119, no. 4, pp. 2382–2393, 2006.

[2] K. G. Niederhoffer and J. W. Pennebaker, “Linguistic style matching in social interaction,” J. Lang. Soc. Psychol., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 337–360, 2002.

[3] D. Reitter, J. D. Moore, and F. Keller, “Priming of syntactic rules in task-oriented dialogue and spontaneous conversation,” 2010.

[4] C. Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil and L. Lee, “Chameleons in imagined conversations: A new approach to understanding coordination of linguistic style in dialogs,” ArXiv Prepr. ArXiv11063077, 2011.

[5] R. Levitan and J. Hirschberg, “Measuring Acoustic-Prosodic Entrainment with Respect to Multiple Levels and Dimensions,” 2011.

[6] R. Levitan, A. Gravano, L. Willson, Š. Beňuš, J. Hirschberg, and A. Nenkova, “Acoustic-prosodic entrainment and social behavior,” in Proceedings of the 2012 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human language technologies, 2012, pp. 11–19.

[7] N. Lubold and H. Pon-Barry, “Acoustic-prosodic entrainment and rapport in collaborative learning dialogues,” in Proceedings of the 2014 ACM workshop on Multimodal Learning Analytics Workshop and Grand Challenge, 2014, pp. 5–12.

[8] N. Lubold, H. Pon-Barry, and E. Walker, “Naturalness and rapport in a pitch adaptive learning companion,” Dec. 2015, pp. 103–110. doi: 10.1109/ASRU.2015.7404781.

[9] R. Levitan et al., “Implementing Acoustic-Prosodic Entrainment in a Conversational Avatar,” in Proc. Interspeech 2016, 2016, pp. 1166–1170. doi: 10.21437/Interspeech.2016-985.

[10] R. Hoegen, D. Aneja, D. McDuff, and M. Czerwinski, “An End-to-End Conversational Style Matching Agent,” Proc. 19th ACM Int. Conf. Intell. Virtual Agents, pp. 111–118, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1145/3308532.3329473.

[11] Z. Rahimi and D. Litman, “Entrainment2vec: Embedding entrainment for multi-party dialogues,” in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, vol. 34, no. 05, pp. 8681–8688.

[12] A. Shamekhi, M. Czerwinski, G. Mark, M. Novotny, and G. Bennett, “An Exploratory Study Toward the Preferred Conversational Style for Compatible Virtual Agents,” Oct. 2017, Accessed: May 28, 2021. Online Available.

[13] R. Levitan, “Developing an Integrated Model of Speech Entrainment,” in Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Yokohama, Japan, Jul. 2020, pp. 5159–5163. doi: 10.24963/ijcai.2020/727.

[14] Levitan, Rivka, et al. “Implementing Acoustic-Prosodic Entrainment in a Conversational Avatar.” Interspeech. Vol. 16. 2016.